Marvel didn’t invent the shared universe.

Neither did DC.

A Texan writing by candlelight in the 1920s beat them all by a century. Academic scholars have a name for it now. Publishers are building an empire on it. And lots of comic readers have no idea it exists.

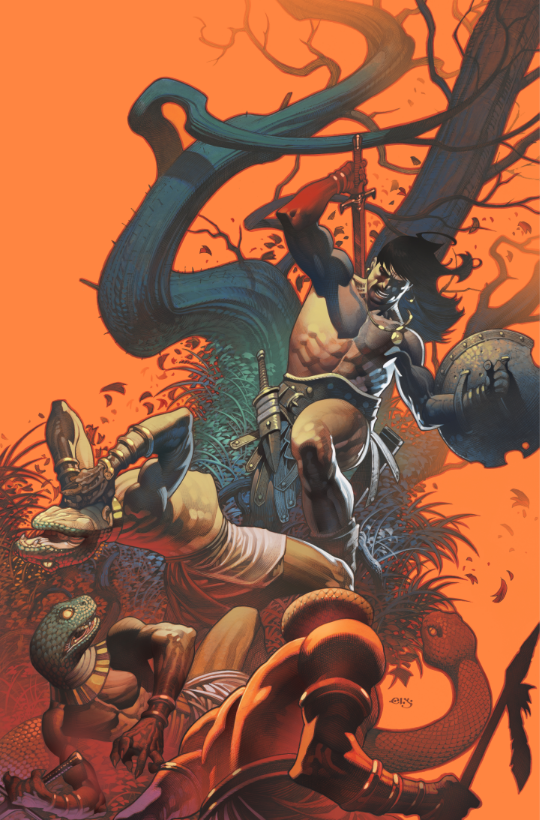

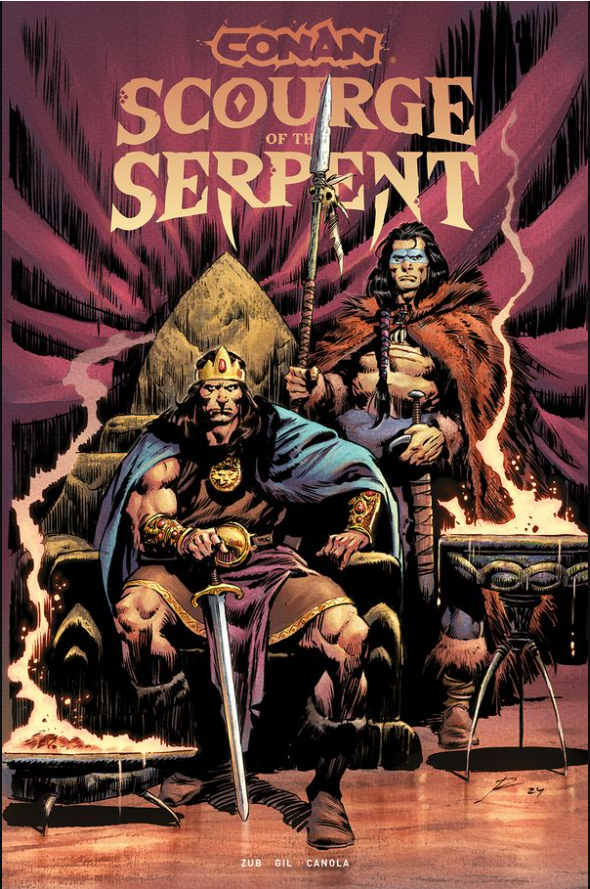

Conan: Scourge of the Serpent is taking three previously unrelated Robert E. Howard stories written across different years, for different magazines, about different characters in different millennia, and proving they were always part of the same cosmic conspiracy.

One that’s been hiding in plain sight since the dawn of civilization itself.

The Original Shared Universe: Before Marvel, Before DC, There Was Howard

Nearly a century has passed since Robert E. Howard sat at his typewriter in Cross Plains, Texas, unknowingly architecting what would become literature’s first true shared universe. Marvel’s interconnected films? DC’s multiverse? Child’s play compared to the vast, blood-soaked world Howard was weaving back when radio was still the height of home entertainment.

Scholar Jeffrey Shanks cemented a name for it: the Howardverse. What began as academic terminology has now become gospel truth for Heroic Signatures and Titan Comics. Here was a writer who refused to let his creations exist in isolation. Instead, he built something grander: a fictional history spanning tens of thousands of years, from the mist-shrouded Thurian Age to the tommy guns and fedoras of the 1930s.

Consider the sheer audacity of Howard’s vision. Rather than vanishing into prehistory, Kull’s Atlanteans evolved, migrated, and, eventually, would be the progenitors of the fierce Cimmerians. Artifacts of terrible power – the Serpent Ring of Set chief among them – surface across millennia, each appearance adding another layer to their dark mythology. Ancient Stygia transforms through the ages into the Egypt we know from history books, grounding Howard’s fantastic prehistory in recognizable reality.

And threading through it all? The Serpent Men, those shape-shifting horrors who serve the malevolent god Set, slithering from age to age, their conspiracy against humanity never truly dying, only adapting, waiting, scheming.

Conan may be the most famous resident of this universe, but he’s far from alone. The Puritan Solomon Kane stalks through the 16th century with pistol and rapier. Dark Agnes de Chastillon carves her legend with French steel and fierce independence. El Borak brings Texas grit to Afghan adventures. Each hero fights their own battles, yet they’re all part of a cosmic struggle between barbarism and civilization.

This interconnected mythology lay dormant in Howard’s tales for decades, waiting for readers to piece together the clues he’d scattered throughout his work. Now, finally, someone has taken those scattered puzzle pieces and assembled them into their intended shape, creating a narrative that demonstrates exactly how these disparate stories form one magnificent whole.

Scourge of the Serpent: Three Timelines, One Epic Conspiracy

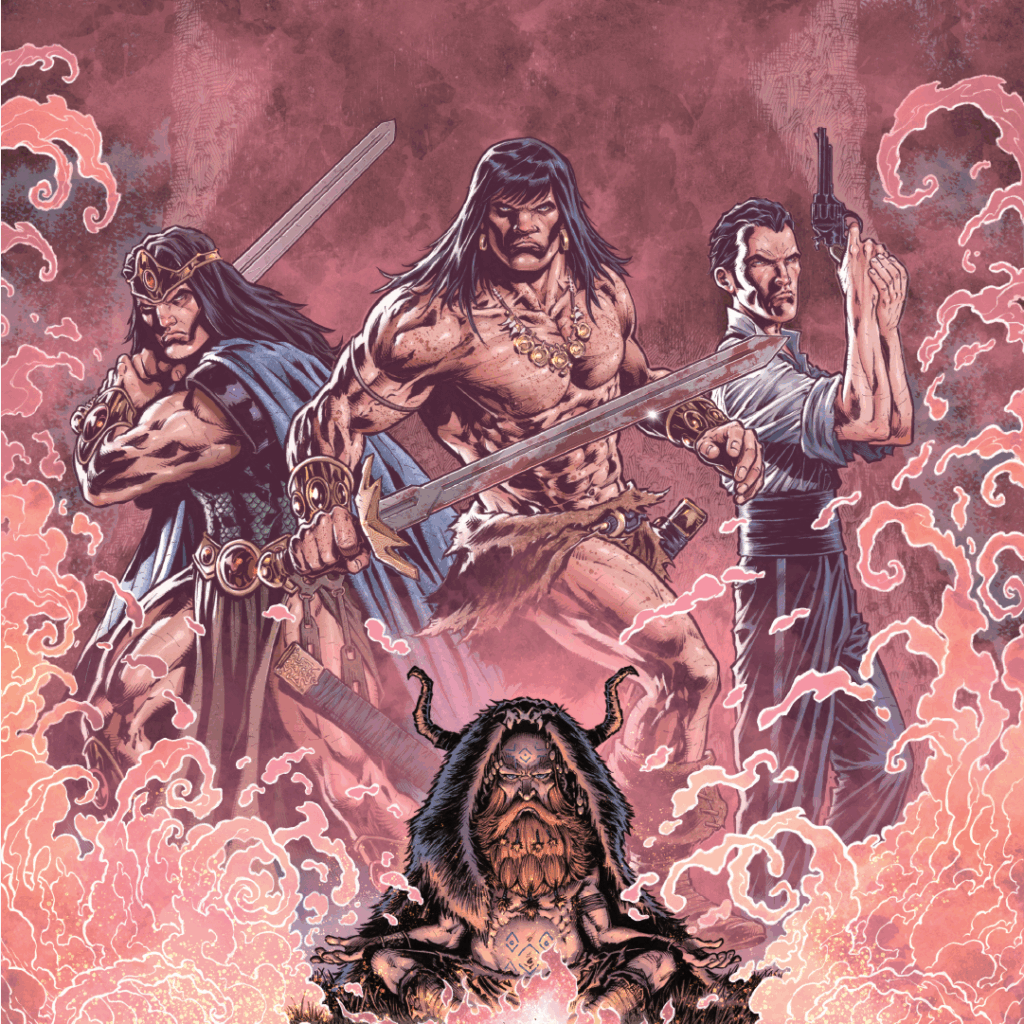

Enter Conan: Scourge of the Serpent, where writer Jim Zub performs an act of narrative sorcery. Forget traditional crossovers where heroes bump fists and trade quips. Zub introduces something far more ambitious: “metaphysical simultaneity,” a concept that transforms three separate Howard tales into a single, time-spanning epic.

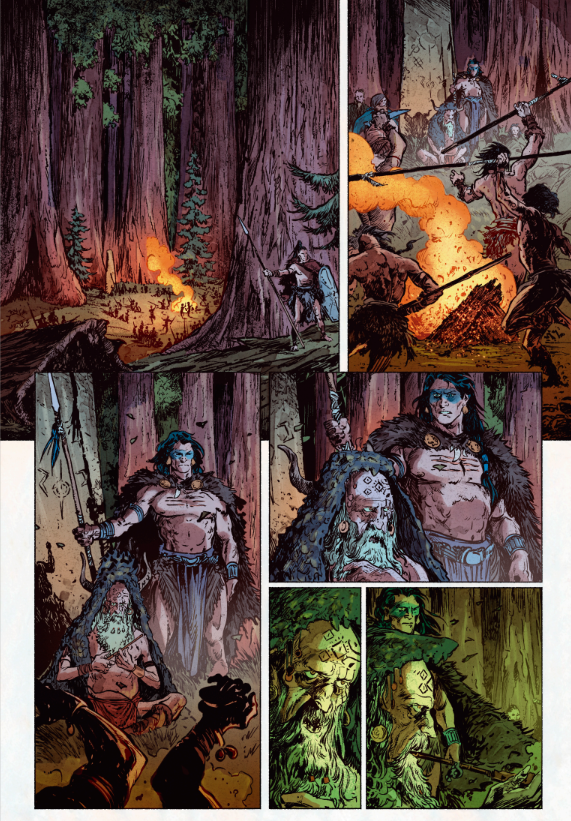

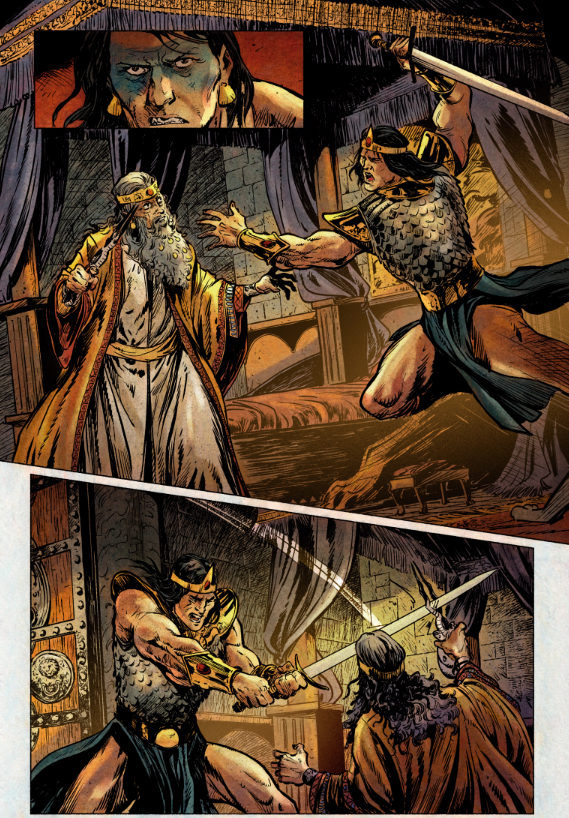

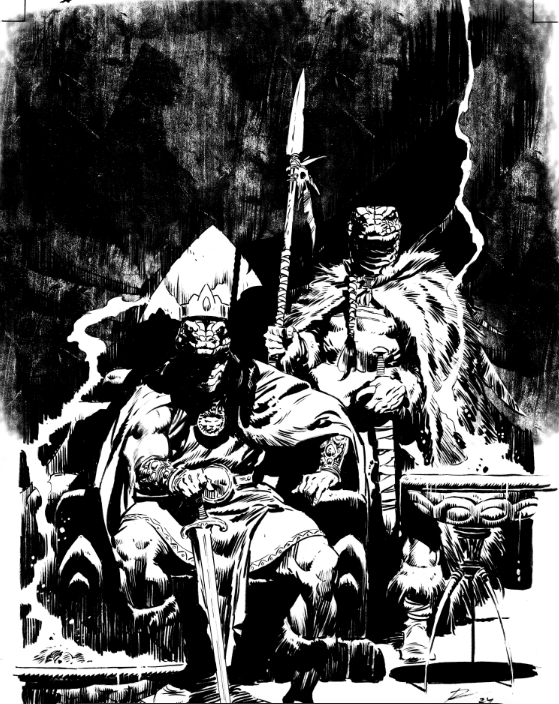

The arc’s genesis starts 100,000 years ago, when King Kull receives a dire warning from his Pictish ally, Brule the Spear-Slayer. The royal court of Valusia has been infiltrated by shape-shifting Serpent Men who’ve replaced his most trusted advisors. “Ka nama kaa lajerama!” – the ancient incantation that strips away their human disguises – becomes Kull’s only weapon against an enemy that wears familiar faces. Howard’s 1929 masterpiece “The Shadow Kingdom” lives again, but now it’s merely one thread in a larger weave.

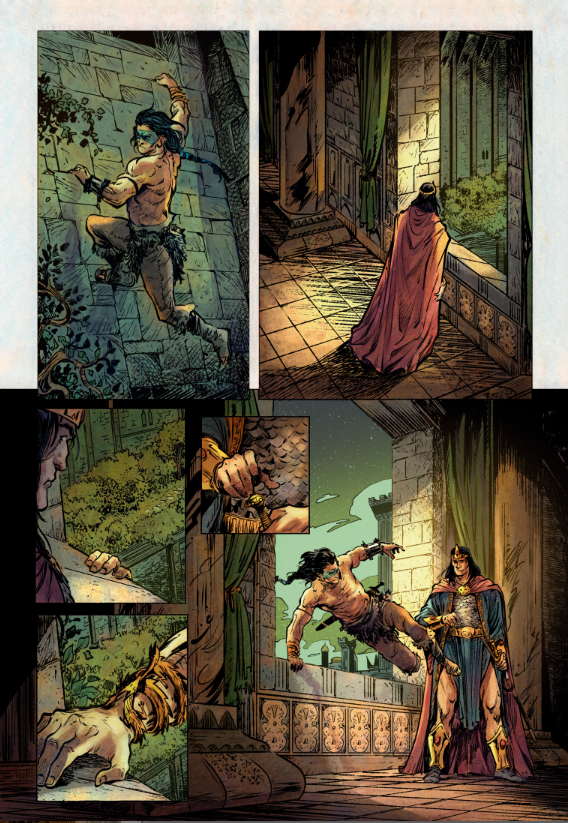

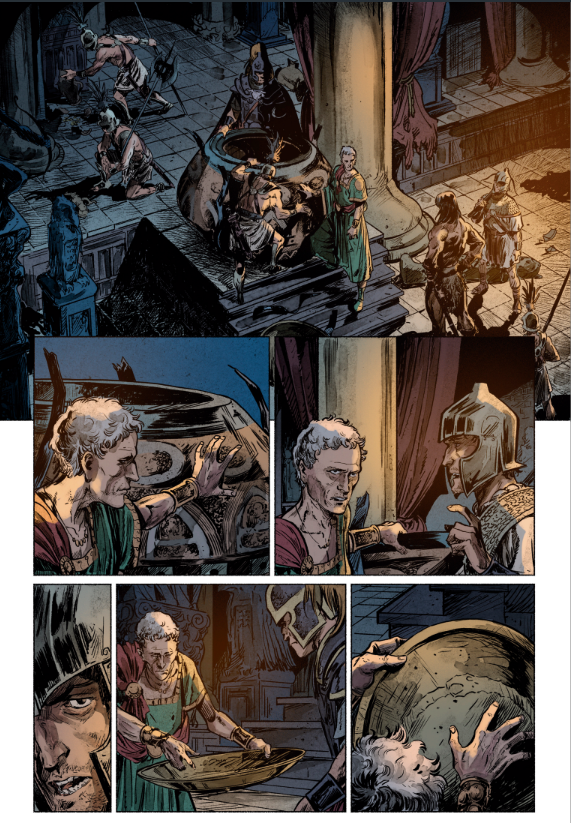

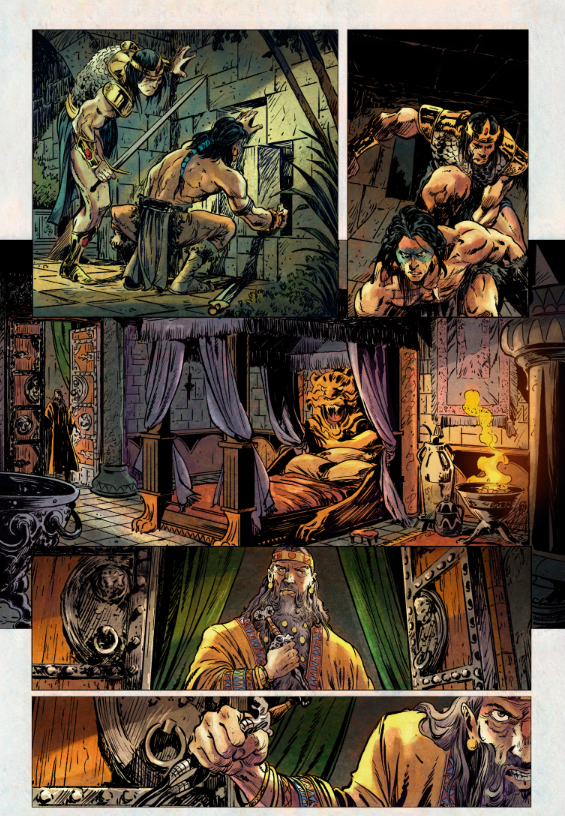

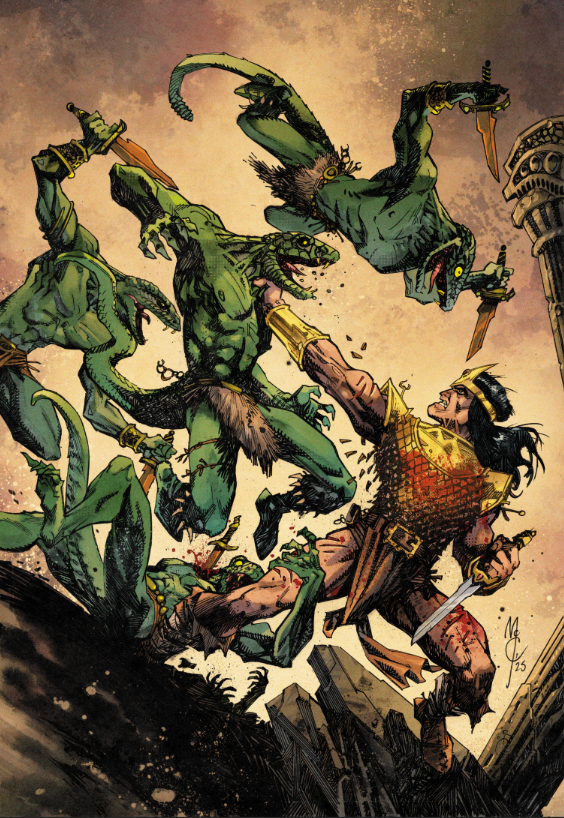

Fast forward to 14,000 BC. An eighteen-year-old Conan – brash, cocky, magnificently stupid in the way only young barbarians can be – breaks into a Nemedian museum to steal a Zamorian goblet. Simple heist, easy money. Except the owner’s already dead, and suddenly our young Cimmerian finds himself framed for murder in an adaptation of “The God in the Bowl.” Here we find the lynchpin of something cosmic, something writhing.

Meanwhile, in a gaslit Boston of 1934, Professor John Kirowan confronts a horror straight from “The Haunter of the Ring.” James Gordon’s wife has descended into homicidal madness after donning the infamous Serpent Ring of Thoth-Amon. Academic curiosity becomes a desperate race against supernatural possession as Kirowan realizes this cursed jewelry is far more than a collector’s curiosity.

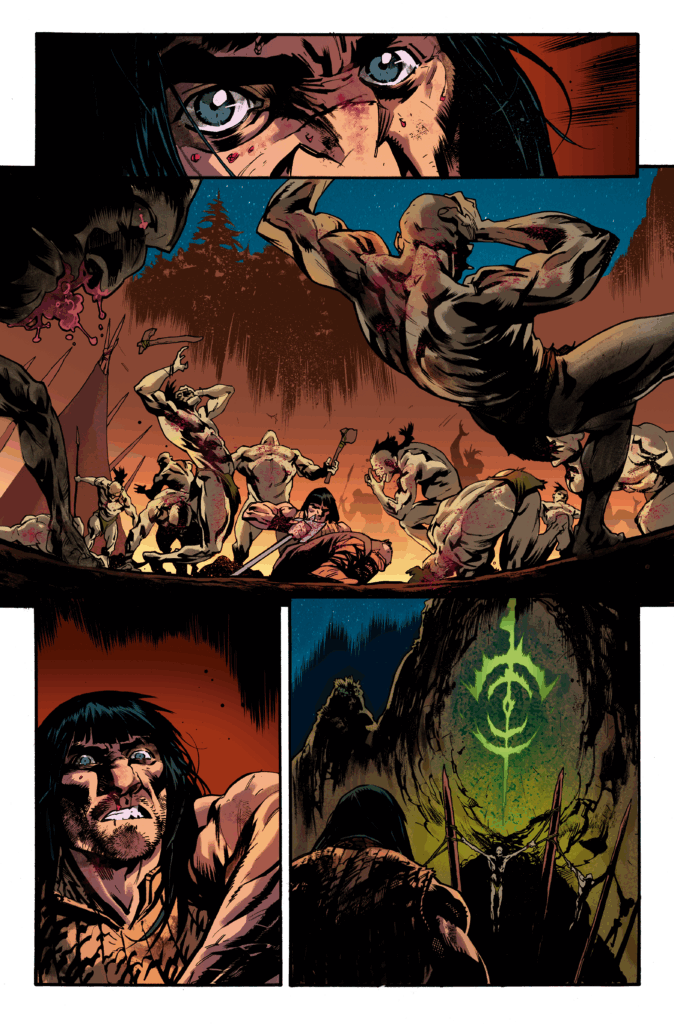

Three stories. Three eras. One conspiracy orchestrated by Set himself, that serpentine god whose coils have been tightening around humanity’s throat since before recorded time.

Binding these narratives together are artifacts pulsing with ophidian power: Brule’s dragon-coiled armband, the cursed Serpent Ring that drives mortals to madness, and the Fangs of the Serpent. These objects actively spin a web where past, present, and future exist simultaneously on some terrible cosmic plane.

The brilliance lies in the revelation that Conan stands unknowingly at the center of Set’s grand design. Every adventure, every seemingly random encounter, has all been building toward an “unspeakable” endgame that threatens every era simultaneously.

Three heroes fighting separate battles across history, each representing a different response to the same primordial threat that has stalked mankind since we first stood upright and gazed at the stars with defiance rather than submission.

The Eternal Struggle: Heroes vs. Serpents Across Time

Why these three?

Out of Howard’s entire pantheon, Zub’s selection reveals a deeper understanding of what the Texan author was truly exploring through his fiction. Kull of Atlantis embodies the paradox of the barbarian-turned-king, wielding power while despising the very throne he conquered. His philosophical nature constantly questions reality itself. “What is real?” he asks, even as serpentine conspirators wear the faces of trusted friends. Here stands barbarism attempting to forge something better from civilization’s corrupt bones, forever an outsider even on his own throne.

Contrast that with eighteen-year-old Conan: unrefined, dangerously confident, operating on pure instinct. This version hasn’t yet learned the cunning that will one day make him king. He crashes into civilized society like a dire wolf through a stained-glass window. Where Kull questions, Conan acts. The Nemedian authorities see a savage, a convenient scapegoat for their murder mystery. They cannot comprehend that his straightforward nature makes him incapable of their sophisticated deceits. Raw vitality meets urban corruption, and the city never knows what hit it.

Professor John Kirowan occupies the opposite end of this spectrum. Product of universities and libraries, he battles with knowledge rather than muscle, confronting ancient horror with research and occult scholarship. In 1930s Boston, swords won’t save you from possession by cursed jewelry. His battlefield consists of dusty tomes and whispered incantations, proving that humanity’s war against primordial evil adapts to whatever weapons each age provides.

The genius lies in how these three archetypes illuminate Howard’s central obsession from every angle. Together, they form a complete treatise on humanity’s relationship with its own nature: the barbarian establishing order, the savage challenging corruption, the scholar defending what civilization has built against forces that would pervert it from within.

And what an enemy they face. The Serpent Men circumvent typical sword-and-sorcery villainy through their methodology. Jim Zub identifies their true horror: they “replace, infiltrate, and corrupt,” transforming society’s own structures into weapons against itself. A trusted councilor becomes an enemy agent. Laws meant to protect become chains of oppression. These creatures embody the deceptive and immoral hierarchies of civilization.

Consider the insidious brilliance of opponents who force each era’s heroes to fight differently. Kull must question everyone, trusting only the barbaric honesty of Brule the Pict. Conan’s straightforward approach becomes both weakness and strength against enemies who hide behind civilized facades. Kirowan must decode centuries of occult knowledge just to understand what he’s fighting.

The ambition to tell a story like this would mean nothing without the execution to support it. Thankfully, the creative team understands that honoring Howard’s legacy requires more than just namedrops and Easter eggs.

From Initial Experiment to Focused Masterpiece

Phase 1 of Titan’s Conan the Barbarian run taught valuable lessons. Battle of the Black Stone united Conan, Dark Agnes, Solomon Kane, El Borak, and James Allison against cosmic horror. Ambitious, yes, but some reviewers called it “overstuffed.” Characters died without weight. The villain felt generic. Titan Comics listened.

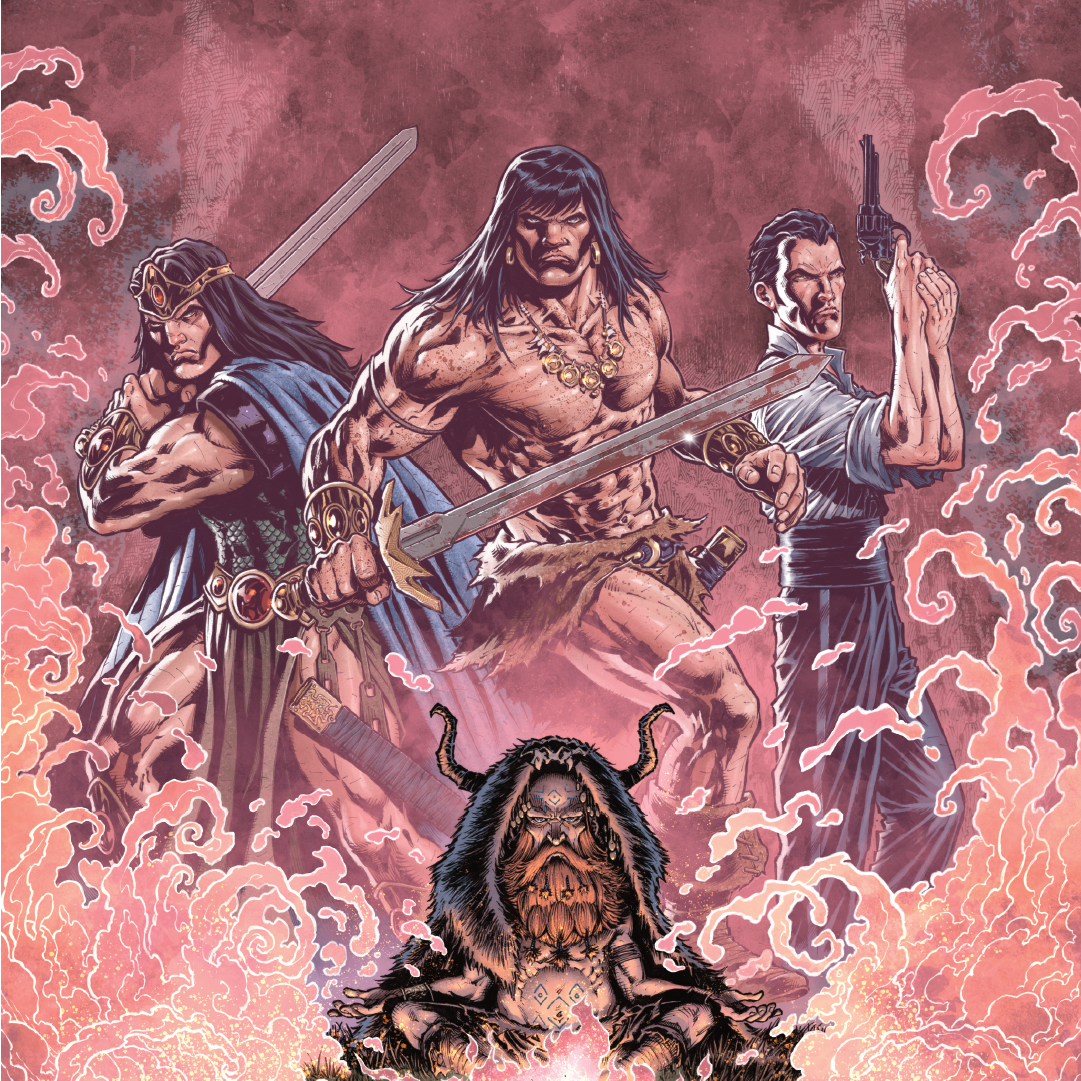

Scourge of the Serpent represents evolution through focus. Three protagonists instead of five-plus allows each hero room to breathe, each timeline space to develop. Jim Zub, who’s mapped out storylines through issue #50 of the main series, demonstrates mastery of both Howard’s prose and long-form comic storytelling. His dialogue captures Howard’s voice without mimicking it. Critics notice: “[he] knows his Howard,” they write.

Ivan Gil’s artwork deserves its own temple in Valusia. Dense backgrounds distinguish each era: Kull’s torch-lit throne room, Conan’s shadowy Nemedian streets, Kirowan’s gaslit Boston. Critics throw around “brilliant” and “gorgeous,” but what matters is that Gil makes readers feel the weight of Kull’s crown, smell the blood on Conan’s sword, sense the mustiness of Kirowan’s ancient books.

Numbers tell the story of this series’ reception. Comic Watch: 9.3/10. Comical Opinions: 9.5/10. Doc Lail Talks Comics: A+. Superhero Hype: 9/10.

Yet the true achievement runs deeper than scores.

New readers can grab issue #1 and immediately understand everything. No Wikipedia required, no back-issue hunting necessary. The refinement from scattered experiment to focused epic demonstrates something crucial: Heroic Signatures and Titan Comics are successfully building something that honors the past while pushing toward an ambitious future.

The Blood-Soaked Future of the Howardverse

Scourge of the Serpent is your gateway into a universe that existed before the term “shared universe” entered Hollywood pitch meetings.

This is where the real magic begins.

Howard built this mythology when your grandparents were young. Now it’s yours to discover.

Whether you’re a longtime Conan devotee or someone who just thinks swords and sorcery sound cool, this four-issue epic opens doors to adventures spanning millennia.

The invitation stands. The only question remaining: will you answer the call that echoes from the Thurian Age to today?