For nearly a century, the grim Puritan avenger Solomon Kane existed only in short stories, poems, and unfinished fragments. No novel. No room to breathe.

That changes now.

Solomon Kane: Suffer the Witch is the first full-length Kane novel ever written. Shaun Hamill–whose debut A Cosmology of Monsters earned praise from Stephen King and whose work has drawn comparisons to Lovecraft–takes Howard’s dour swordsman into territory the original stories never explored: an aging body, a faith riddled with contradictions, and a witch trial where the accused is guilty of magic but innocent of murder.

We sat down with Hamill to talk about what drew him to Kane, how he approached writing a character defined by moral absolutes, and why a Puritan who hated Christmas ended up facing a Welsh horse-skull demon on Christmas Eve.

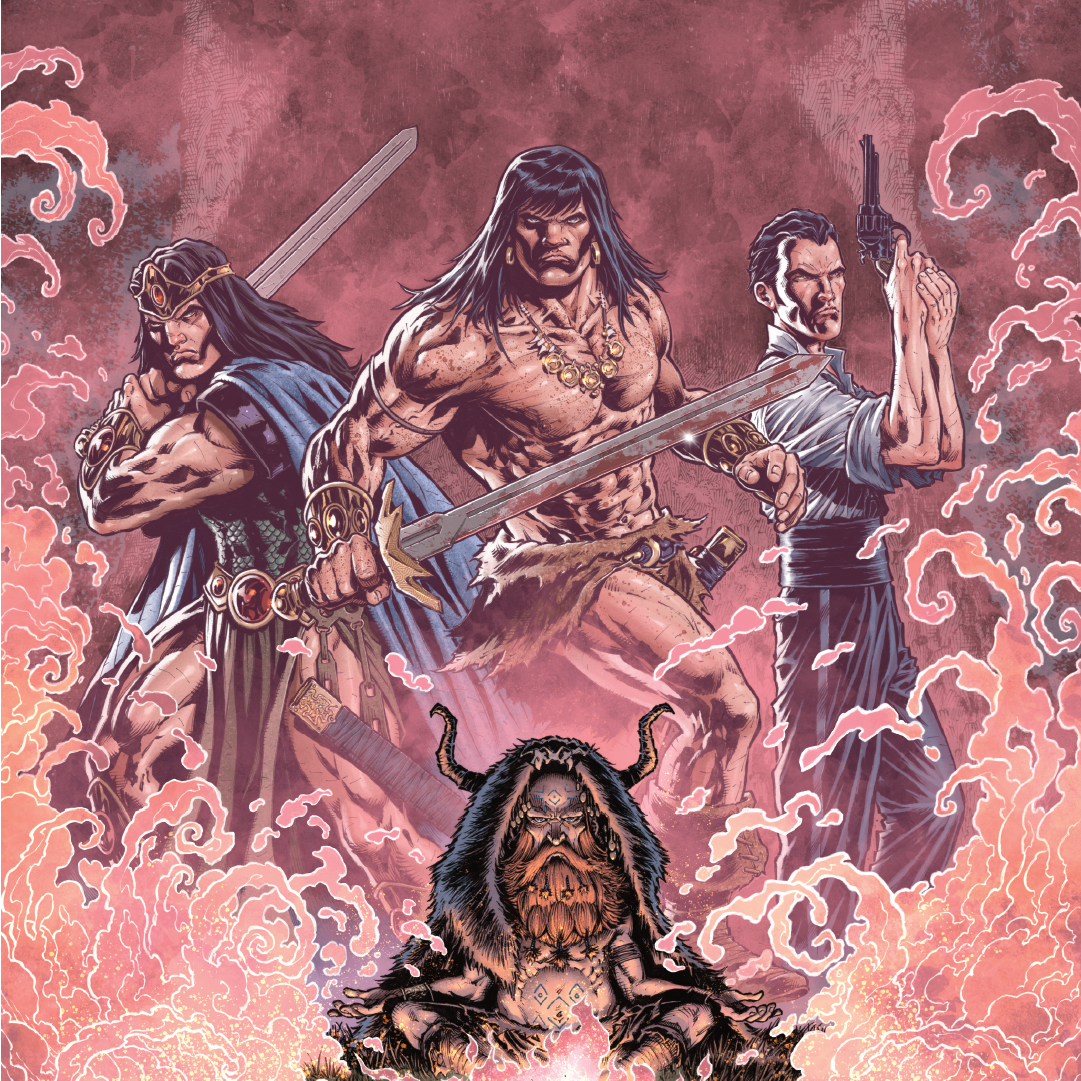

Before there was Conan, there was Solomon Kane.

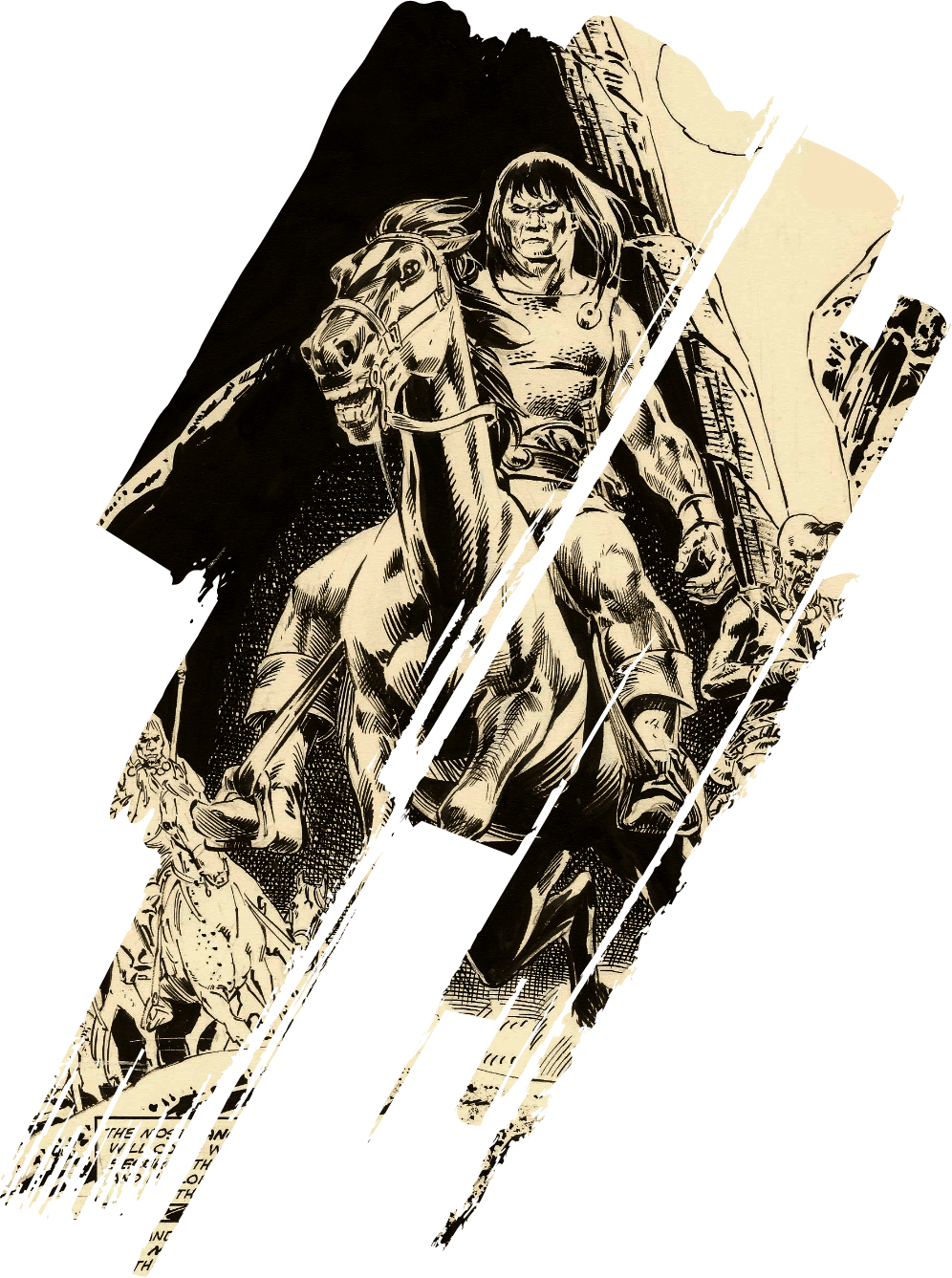

Robert E. Howard created his grim Puritan wanderer in 1928, four years before the Cimmerian would storm onto the pages of Weird Tales and change fantasy fiction forever. But while Conan conquered, Kane remained in the shadows. Nine short stories. A handful of poems. Fragments and drafts that never saw completion in Howard’s lifetime.

For nearly a century, that was all we had.

Solomon Kane: Suffer the Witch changes that.

Released on January 6, 2026, it marks the first full-length novel in the character’s history, and the writer Heroic Signatures chose for the job didn’t come to Kane as an afterthought. He came to Howard through Kane in the first place.

“The first book of Robert E. Howard stories I ever read was the Del Rey collection The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane,” says Shaun Hamill, author of the Stephen King-praised A Cosmology of Monsters and The Dissonance. “I can’t remember how I found out about the character, but I remember being quite taken with the concept of a puritan knight-errant battling supernatural evil.”

That initial fascination led Hamill deeper into Howard’s work, but it started with the dour swordsman in black. It’s a fitting origin for the writer now tasked with giving Kane his first novel.

There’s another connection, too. “I feel a bit of kinship with Howard,” Hamill admits. “Like Howard, I’m from Texas, and I also spent thirty years of my life wishing I was away on grand adventures rather than living with my parents. It’s why Suffer the Witch is dedicated to Howard, and why the novel includes an homage to him, in the character of Paul.”

A Texas writer, shaped by restless longing, dedicating his first Kane novel to the Texas writer who created him. The symmetry matters. But what matters more is understanding who Solomon Kane actually is and why he’s proven so much harder to write than his more famous barbarian counterpart.

Understanding Kane

Howard described his creation as “a strange blending of Puritan and Cavalier, with a touch of the ancient philosopher, and more than a touch of the pagan.” Tall, gaunt, dressed entirely in black save for a bright green sash. Cold eyes beneath a slouch hat. A rapier at his hip and a hunger in his soul that drove him ceaselessly forward not for gold or glory, but to “right all wrongs, protect all weaker things, avenge all crimes against right and justice.”

On the surface, the comparison to Conan seems obvious. “Kane shares some similarities with Conan, in that both are adventurers who travel the world and come into brutal, violent conflict with human and supernatural enemies,” Hamill acknowledges. But the differences run deeper than setting or costume.

“Conan’s adventures take place in a fantasy prehistory,” Hamill explains. “Kane moves through a very real, if fictionalized, part of human history.” The Hyborian Age has no rules except what Howard invents; Elizabethan England and the African coast carry the weight of actual geography, actual theology, actual consequence.

Then there’s the matter of constraint. “Conan is a creature of passion, following his own inner compass. There’s nothing Conan won’t do, if he wants or needs to do so. Kane is a bit more considered in his actions.” The barbarian takes what he desires. The Puritan wrestles with what he’s permitted.

Hamill confesses that his understanding of Kane evolved through the writing itself. “I originally believed that Kane’s setting and religion were the sole thing separating him from Conan. But after traveling alongside Kane for a while, and forcing him to answer some tough questions, I no longer believe that.” What changed? “I think that Kane has a real vested interest in understanding good and evil, and wants to do good. He comes at the good in savage, harsh, brutal ways, but has a deep-seated morality that I admire.”

A deep-seated morality. A worldview drawn in black and white. So what happens when you force a man like that into shades of gray?

The Premise of Suffer the Witch

The premise of Suffer the Witch sounds almost classical: a woman accused of witchcraft in a small English village, facing execution for a string of grisly murders. Solomon Kane arrives to investigate. Justice will be done.

But Hamill isn’t interested in a simple wrongful accusation narrative. Sybil Eastey is a witch. She’s simply not the killer.

This is where things get complicated for Kane, and for readers expecting pulp simplicity. “Kane is a bit of a contradiction,” Hamill notes. “He’s Christian, but carries a pagan magic staff. He counts a pagan priest as his blood brother. I wanted to explore that contradiction in more explicit terms, and put Kane through a bit of a moral wringer, force him to face the gaps between his actions and beliefs.”

A real witch, falsely accused of murder. The crime is real. The magic is real. The guilt is… partial? How does a man who sees the world in absolutes navigate that terrain?

Hamill found his answer in Sybil herself. “She’s a bit of a play on Catwoman or Irene Adler,” he says, “a female counterpart for Kane who sits across an ideological divide from our hero. She vexes and challenges him, pointing out some of the contradictions he lives by.”

It’s a shrewd pairing. Kane has faced demons, vampires, ancient horrors risen from pre-human civilizations. But an adversary who holds up a mirror? Who forces him to justify his own moral compromises? That’s a different kind of threat entirely.

And Kane faces it at a disadvantage. This isn’t the unstoppable avenger of Howard’s earliest tales, the man who could pursue a bandit across continents on sheer righteous fury alone. This Kane is older. His body has started to betray him.

Kane is in his fifties now. His hair has gone gray. A bad knee dogs him throughout the novel, a constant reminder that the flesh weakens even when the spirit refuses to yield.

“I was interested in a story that checked in on Kane later in his life, when his hair is going gray and his body is beginning to trouble him,” Hamill explains. “How does the savage warrior cope, when he ages out of the role, and is no longer the youngest and most powerful body on the battlefield?”

Then the question that defines the novel: “If you strip him of that, what’s left?”

What remains is faith. Conviction. A lifetime of hard-won alliances and harder-won wisdom. Kane can no longer simply overwhelm his enemies, for he now must outthink them, outlast them, and draw on resources beyond the physical.

Which raises its own complications. Because the resources Kane has accumulated over decades of wandering aren’t strictly Christian. The staff he carries came from an African shaman. The blood brother he trusts most practices magic that should damn them both. And the novel, Hamill promises, doesn’t let Kane look away from that contradiction any longer.

The Darkness Within Solomon Kane

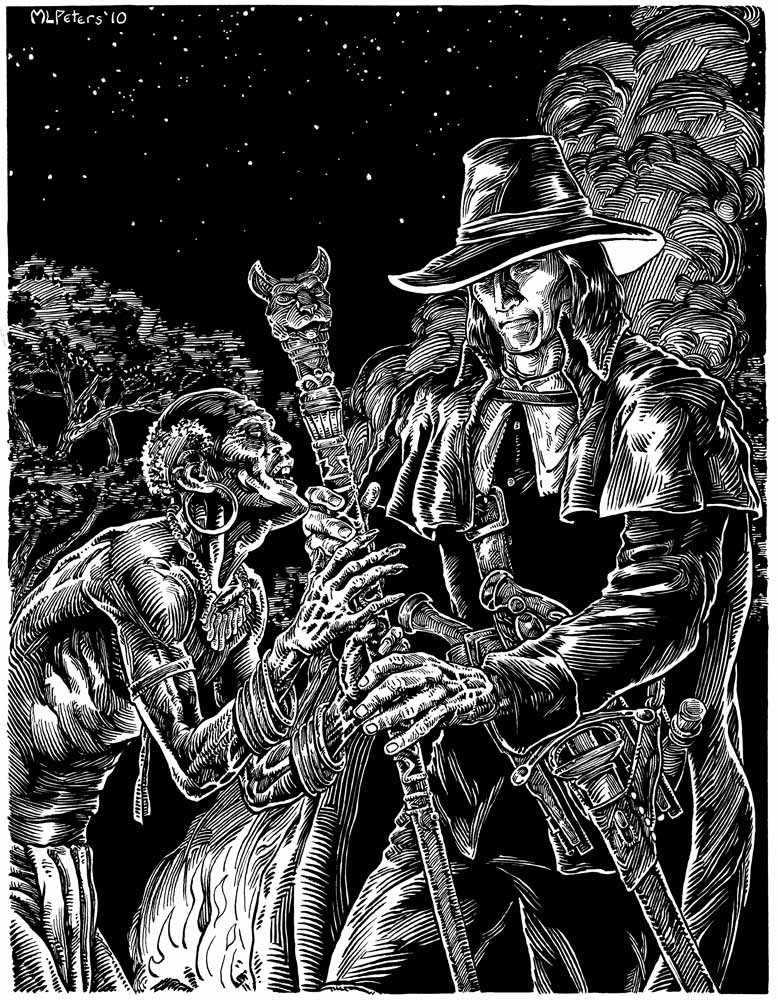

In Howard’s original stories, the relationship between Kane and N’Longa–the African shaman who becomes his blood brother and gifts him the mystical Staff of Solomon–exists in a fascinating state of tension. Kane accepts the alliance. He wields the staff. He never fully reconciles either with his professed faith.

Howard left that tension productive but unexamined. Hamill doesn’t.

“Without giving too much away, the novel deals with that contradiction very explicitly,” he says. “Kane is forced to reckon with his own cognitive dissonance, and it is a major plot thread in the novel.”

Cognitive dissonance. It’s a clinical term for something Kane has been living with for decades: the gap between the Christianity he professes and the pagan power he employs. Suffer the Witch closes that gap, or at least forces Kane to stand in it and look around.

The novel also expands what we know of Kane and N’Longa’s partnership. “We get to see how [their relationship] evolved across the decades,” Hamill explains. “I liked the idea of them working together regularly, becoming partners on a quest to stamp out evil around the world.”

Not a single encounter. Not an uneasy truce. A genuine partnership, forged over years of shared purpose. Two men from radically different traditions, united by the conviction that evil must be opposed wherever it takes root.

This is only one thread Hamill pulls from the original canon, for Suffer the Witch is also laced with connections to Howard’s stories, small nods and deliberate extensions that reward readers who know where Kane has been.

Easter Eggs in Suffer the Witch

“I tried to draw from all the original stories and fragments wherever I could,” Hamill says of his approach to continuity. “I didn’t completely succeed, but I managed to get in a lot of small nods and references to Kane’s past.” It’s one reason the novel is set late in Kane’s career: so there’s more history to reference and more weight to the man’s weariness.

But Hamill brought something to the table that goes beyond research. “I grew up the son of a preacher,” he reveals, “and although I am no longer a believer, I still find Christianity fascinating. I wanted to pull some subtler threads of the canon to the surface in this novel.”

One method: setting. Suffer the Witch takes place in an English Puritan village so that Kane is among his own people, at least nominally. “What do they make of this man who dresses as they do, and who professes to share their beliefs, but whose life and experiences are so different from their own?” It’s a question Howard never asked. His Kane was always the outsider, the wanderer passing through. Hamill’s Kane comes home, and home doesn’t quite recognize him.

The result, however, is anything but imitation. “I didn’t try to write a Robert E. Howard story,” Hamill clarifies. “I tried to write a good Solomon Kane story, staying true to the world and character as Howard wrote them, but using my own voice and rhythms. Hopefully the end result works for longtime fans without seeming too much like a xerox of the originals.”

Suffer the Witch isn’t Hamill’s only contribution to Kane’s legacy, either. Weeks before the novel’s release, readers found Kane in unfamiliar territory: a Welsh village at Christmas, a season the historical Puritans despised, and a threat drawn from folklore Howard never touched.

The Lair of the Mari Lwyd

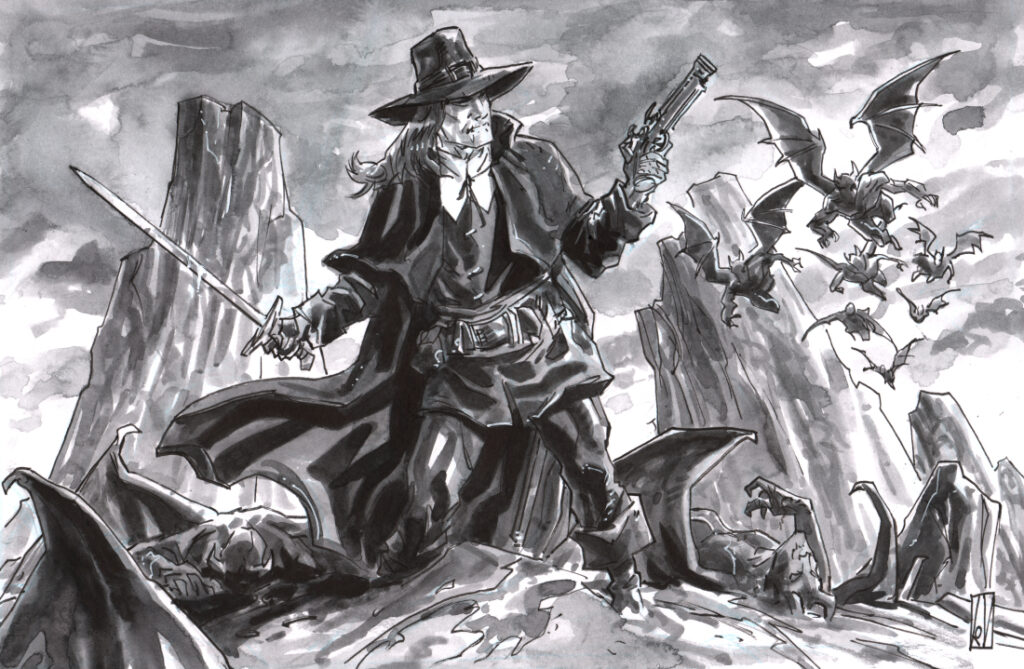

The Lair of the Mari Lwyd, available now as an ePub, drops Kane into altogether stranger territory.

The Mari Lwyd is a Welsh wassailing tradition dating back centuries where a horse’s skull is mounted on a pole, draped in white cloth, and decorated with ribbons and glass eyes. Groups carry it door to door during the Christmas season, demanding entry through song. Householders must respond in verse, trading rhymes until one side relents.

It’s eerie, festive, ancient, and deeply rooted in pre-Christian custom.

Hamill’s discovery of it was considerably less romantic. “I first saw the Mari Lwyd in a clickbait article about spooky Christmas traditions,” he admits. “I thought it looked neat but didn’t give it much more thought.”

Years later, the image resurfaced at exactly the right moment. “When Titan and Heroic asked me if I’d like to write a Solomon Kane short story, and told me the story would be coming out in late 2025, I asked if I could do something with a Christmas theme.” The irony was irresistible: “Solomon Kane is a Puritan, and Puritans hated Christmas. It seemed too much fun to pass up. Once that decision was made, the Mari Lwyd wasn’t far behind. How could I resist such a striking, dramatic figure?”

The challenge lay in transformation. The traditional Mari Lwyd is mischievous instead of menacing. “I don’t want to give away the whole story,” Hamill says, “so I’ll say this: anyone familiar with the Mari Lwyd tradition will not be offended by the course of the tale. I did my best to honor the mischief and fun of the real tradition, while also giving Kane a dangerous and terrifying foe who looks like the Mari Lwyd but behaves in an upsetting manner.”

Read Suffer the Witch and The Lair of the Mari Lwyd Now!

Writing the novel changed Hamill’s understanding of its protagonist. “What surprised me, as I wrote the novel, was how it became an examination of one central question: Who is Solomon Kane, really?” He pauses. “I won’t completely relay my answer to that question here, because I don’t want to spoil my own novel for readers.”

Fair enough. Nearly a century of waiting; readers can discover that answer themselves.

One reviewer, finishing an advance copy, wrote: “If I were Titan Books, I’d keep Shaun Hamill writing new Solomon Kane adventures.” Hamill, it turns out, would welcome the opportunity.

“If Suffer the Witch does well, and the fans enjoy it, I would love to tell more Solomon Kane stories,” he says. “I’ve missed him since turning in The Lair of the Mari Lwyd, and have a few ideas scribbled down in case I’m invited back to the party someday.”

Ideas scribbled down. A writer who misses his character. A Puritan wanderer who finally has room to stretch beyond the confines of short fiction.

Solomon Kane walked alone for almost a hundred years. He doesn’t have to anymore.

Both stories are available for reading now!